I don’t mean to be apocalyptic here, in the face of the terrible tragedy hitting the Japanese people. But I think the current crisis is going to accelerate the aging of Japanese society, especially if the nuclear disaster gets worse. And I’m wondering whether we are seeing the beginning of the end of Japan as an industrial power.

Think about this from the perspective of an executive running a major Japanese manufacturer. In the short-term, when you are facing all the problems at home, you may find it appealing, wherever possible, to ‘temporarily’ switch over much of your production to either China or the U.S., your two major markets. This can be justified, patriotically, as the need to keep up profits to help fund the reconstruction of Japan.

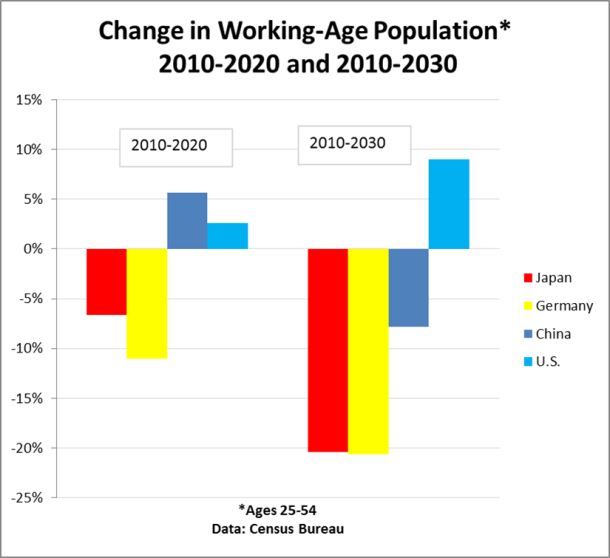

But you may not want to move that production back again. In the medium-term, as you consider how much to invest in rebuilding your factories and infrastructure in Japan, you will face a demographic problem–the coming collapse of the working-age population. Take a look at this chart:

Basically, Japan’s working-age population is anticipated to drop by 20% over the next 20 years. And that actually understates the problem in the rural areas, which have felt a youth drain to the big cities. ( see here and here ).

That makes it much more attractive to invest in China and the U.S., of all places, which have more desirable demographics for both the workforce and consumption. Ten years from now, much of what is made in Japan today will be made elsewhere.

Besides Honda and Toyota, I can’t think of any significant Japanese companies. Hyundai, Samsung in neighboring South Korea are killing it right now.

Sony, Nomura, Mitsubishi UFJ, Nissan, Canon, Sumitomo…

Komatsu is the 2nd largest producer of heavy equipment in the world. dude is very ignorant.

Why exactly was the upper bound of “working-age” set to 54? Seems really low. how to the numbers look if the upper bound is set to 60? 65? Any difference?

Looks the same. For Japan, the 25-64 age group falls by 10% over 10 years and 16% over 20 years

It’s because of age discrimination. In line with the post’s topic, you have to interpret “working age” as “the age where you can still get/retain a job” (in your first career). Tongue only half in cheek …

My prior remark is meant to be more serious than facetious. Especially in tech and industry, a lot of investment in careers and experience is burned by age discrimination. The primary mechanism seems to be that the about once a decade busts lead to job loss in many industries, and in the subsequent recovery older workers are shunned, citing allegedly obsolete skill sets. Automation, offshoring, and technology churn play into it too. Of those, automation and offshoring also limit job opportunity at the entry level. Then a decade later you have relatively fewer people with a decade of industry experience.

But all this of course indicates relatively higher domestic productivity, which should counterbalance the decline in working age population brought about by family unfriendly social environments. I suspect in good part scare-mongering in support of cutting retirement benefits.

So what if the population falls? Innovation keeps driving increased productivity, so Japan’s GDP per capita will continue to increase, and thus the national output will increase or stay the same. And with fewer children coming along, working adults will be able to work a greater part of the time, and with better health, people will be able to work longer.

Or are you suggesting that only growth can sustain a population, and that a stable population is one headed to economic doom?

I said “industrial power.” I didn’t say anything about GDP. At the margin, when Japanese industrial companies decide whether to put more money into factories in Japan or in China, they will chose the place where they can get young workers.

This is true of old style labor intensive manufacturing. But with modern highly automated manufacturing processes I wouldn’t bet on your thesis.

Well if we don’t count in the catastrophe that happened in Japan, this is how Economist saw the Japanese companies going abroad. It’s a good article, ans still who knows whether it will become reality or not.

http://econ.st/gzF7cU

Two questions about the chart:

1. I thought China’s working-age population was supposed to decline from 2015…?

2. Why the acceleration in U.S. population growth?

China’s working age population does decline..hence the negative bar.

I said “industrial power.” I didn’t say anything about GDP. At the margin, when Japanese industrial companies decide whether to put more money into factories in Japan or in China, they will chose the place where they can get young workers.

We see more and more “automated processes” or robotis in industry, requiring less workers per units produced. Specially in high tech, high quality industrial products. I think workers are just one component of the equation. Lets consider culture, engineer, organisation and management capabilities.

Even though the nuclear disaster gets worse to become a Three Mile Island, the development of the Japanese economy still depends on what policy it will adopt from now on.

The ageing trend of the population has been consolidated for the last couple of decades when the capital is shifting to the speculation from the domestic enterprise. There is a structure that has been encouraging the shift, especially in tax system and corporate ownership. In this context, you must understand that shifting the production to the foreign enterprise is part of the speculation.

Thus, a static assumption will be that Japan will maintain the structure to let the population age and die out. That is a fruit of inelastic economic policies Japan have been adopting in turn – namely, the American Keynesianism in 1790-80s, the Neoclassical Synthesis in 1990s-2000s and the New Classical economics in the recent couple of years. Each of these policies sets a target in a variable such as the GDP growth and then concentrates resources to achieve the target at the cost of other variables. Those inelastic policies can also be regarded forms of operations research. Naturally, they cause capital and human misallocations. The dwindling birth-rates are one of the results of the inelastic policies adopted in turn so far.

On the contrary, a kinetic assumption may be that Japan may suddenly revolt against the ‘gaiatsu’ (i.e. pressure from the United States) to get the structure back to the pre-1990 model of economic development to shift the money supply from the speculation to the domestic enterprise to increase the real wages and have more kids. The most likely phenomenon with the policy-change is that the weighted average of capital costs of the Japanese economy will stagnate on the real basis while you see a higher average rate of GDP growth than before. In that case, things are going in the right direction.

Please read ‘the American Keynesianism in 1790-80s‘ as ‘the American Keynesianism in 1970-80s‘. Sorry for the typo.

Just stumbled by looking for data on Japan’s working age population. Could it be that Japan’s falling workforce positions it perfectly for the rise of the machines? Given Moore’s Law, not to mention the so-called singularity, is there any reason to believe that Japan’s productivity cannot increase by 20% over the next twenty years to offset the loss of grunts? Germany’s workforce has been shrinking, too, but it’s economy is strong. Sometimes, less is more…

Demographic situation is problem of all countries of developed world, Soon also China will face with problem of ageing society. Automotove and electronic japanese companies are facing strong competition from Korea and other parts of the world, however I think that Japan will stay important economic player for now.

Wonderful website. A lot of helpful information here.

I am sending it to a few buddies ans also sharing in delicious.

And naturally, thanks to your sweat!